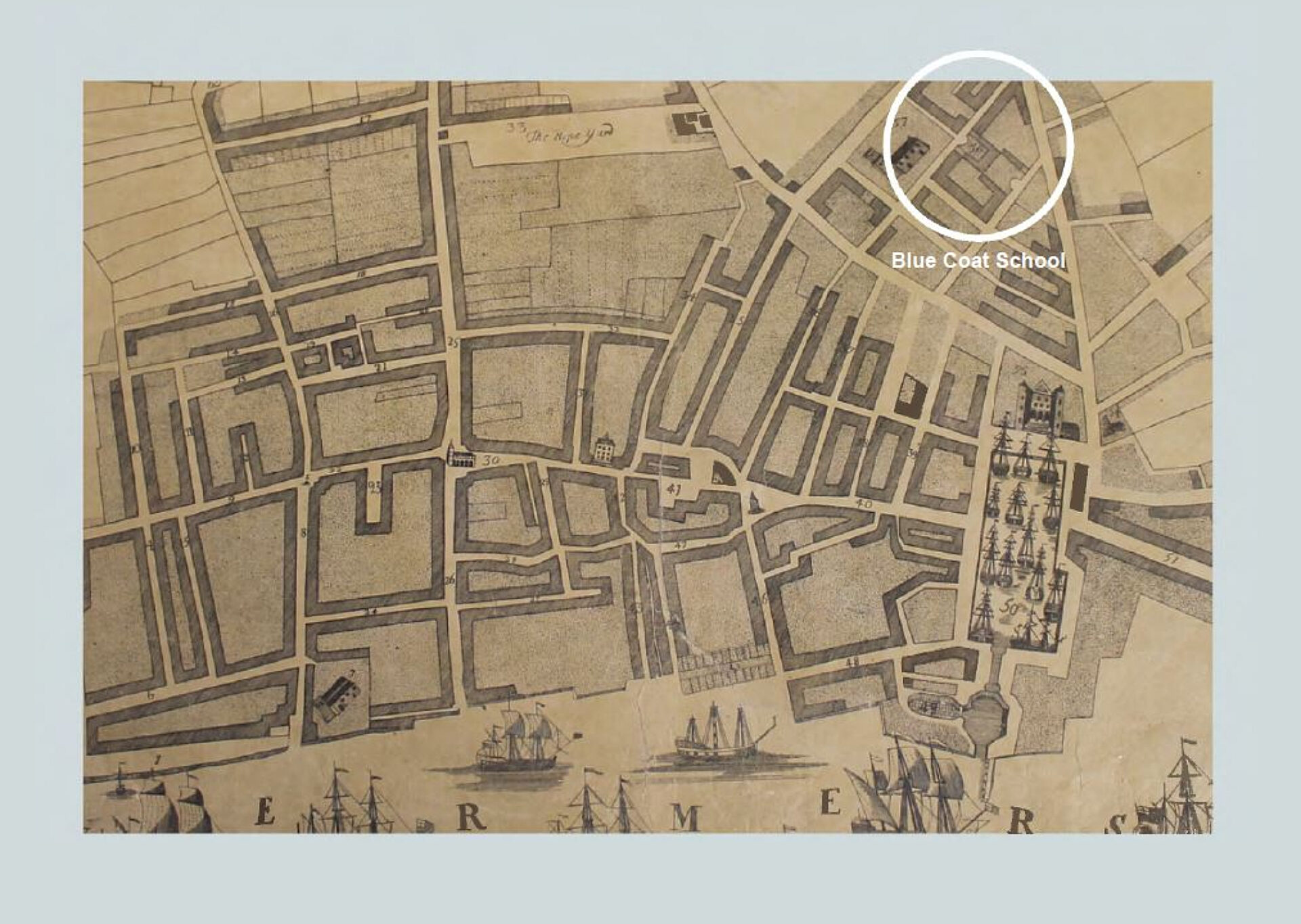

As part of the 300th birthday of the Bluecoat building in 2017, we started a process of interrogating the origins of this former charity school building, founded in the early eighteenth century as Liverpool began its journey towards becoming a port of global significance. We worked with the present Blue Coat School in Wavertree, where the institution relocated to in 1906, and Liverpool Record Office, which houses archival collections relating to our building’s history. Much material was digitised, with support from the National Lottery Heritage Fund, and this is now available on our website.

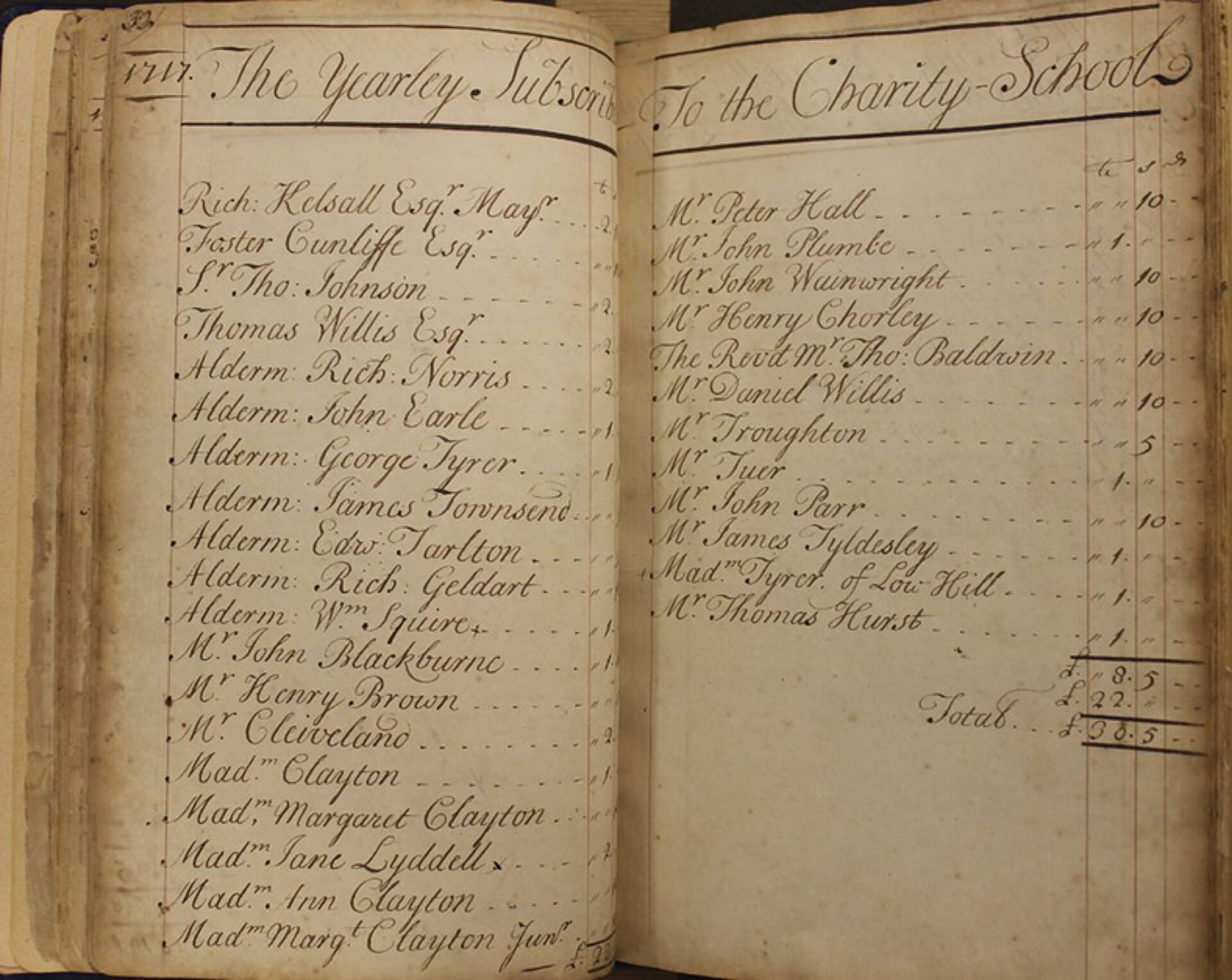

Dr Sophie Jones, then a PhD student at the University of Liverpool, had carried out some research into how the school was funded, examining the accounts books and looking at particular individuals, many of them Liverpool merchants, who donated funds through subscriptions, as well as other sources of income that contributed to the founding and maintenance of Blue Coat (it was spelled this way and often referred to as the Blue Coat Hospital or, simply, the Charity School).

Sophie’s conclusions were summarised in a brochure that breaks down the income into percentages. It was clear that a considerable amount was derived from the transatlantic slave trade, which many of the town’s merchants were involved in, either directly as slave ship owners, or in associated marine trades, or as traders in the goods that slavery enabled in the Caribbean or American colonies, such as sugar, cotton and tobacco.

One figure is central to the founding and growth of the school, master mariner Bryan Blundell (1675–1756), who was also its treasurer, a position that passed on to his sons. There has been much speculation as to the extent to which the Blundell family’s involvement in the trade in enslaved Africans benefitted the school. The present-day Blue Coat School is going through a process of historical research into Bryan Blundell and his association with transatlantic slavery, as part of a review of how he is remembered, for instance in the naming of one of the school’s houses. This review was in response to a local Black Lives Matter campaign for the school to acknowledge and address Blundell’s connections to slavery.

The original Georgian school building that was repurposed as an arts centre in the early twentieth century stands as a symbol of Liverpool’s colonial era. As custodians of the building, the oldest in central Liverpool, we have a responsibility for telling its story. Alongside working with artists and communities to interrogate our history, we also do this through academic partnerships, and we are pleased to be working with Michelle Girvan, the recipient of a Collaborative Doctoral Award with University of Liverpool. She has generously made available her research into Bryan Blundell, which she has carried out as part of her PhD study.

This is available in full here, while this blog summarises some of its key points. Michelle unpicks the description of the Blue Coat School made in 1861 by historian John Hughes as a ‘monument to the charity and piety of its founders’. She charts Blundell’s pivotal role, initially in founding – together with Liverpool’s first joint rector, Revd. Robert Styth - a school for indigent and orphaned children, a philanthropic venture that was representative of a wider charity-school movement across the country from the late-seventeenth century.

Blundell continued his involvement, being instrumental in the construction of the school’s new boarding facilities that replaced the original, more modest day-school building. He was Trustee and Treasurer for 42 years and was succeeded by his sons, Richard (1756–60) and Jonathan (1760–96) for a further 40 years. A commemorative monument in St Nicholas’ Church on behalf of Blundell and a portrait (now on display in the Blue Coat School), commissioned upon his death, cemented his legacy in relation to the school.

Michelle’s research provides a more thorough insight than has been possible to date into the man who helped shape, maintain and govern Liverpool’s eighteenth-century charity school, while looking into his role in the political and mercantile life of Liverpool. While his early biography is sketchy we know that Blundell was apprenticed to sea in 1687, aged twelve, and lost his father at an early age. One of his earliest seafaring experiences involved transporting soldiers to Londonderry, likely in support of William of Orange. A journal he kept right up until his death in 1756 provides a rare insight into the life of an eighteenth-century Liverpool mariner and merchant, and offers a wealth of information about his character, morals, religious fervour and career, which included being taken prisoner, with his crew, by a French privateer in 1706. Michelle draws on this journal to examine Blundell’s early seafaring experiences, from cabin boy to master, and the subsequent wealth he derived from ‘shrewd business acumen, opportunism, meticulous record-keeping and impressive navigational skills’. His wealth is substantiated in his will, which includes assets in property ownership, shares in a local ropery, and numerous ships and stock, alongside his mercantile income.

Like other maritime merchants of the town, Blundell participated in Liverpool’s civic, religious and charitable life, and he had a successful political career as a member of Liverpool Corporation, bailiff, alderman and twice as Mayor, a tenure that was not however without controversy, nor criticism for the zealous piety he exerted, such as building a cage, ducking chair and stocks ‘to ensure that profanity was properly punished’ in the expanding seaport with its attendant vices. His journal also reveals the indispensable networks he was able to access, nurturing relationships with many of Liverpool’s leading merchants including Sir Thomas Johnson, Richard Gildart, John Cleiveland, John Earle, Foster Cunliffe and William Clayton, all of whom he persuaded to support the Blue Coat.

Blundell transported indentured servants to the Americas up until 1698, when the London Royal African Company’s official monopoly on the slave trade ended and Liverpool merchants were able to exploit this new market. Although he makes little explicit mention of this in his journal, Blundell’s involvement in the transportation of enslaved Africans, and his connections to goods that utilised slave labour, implicate him in the port’s slave economy. As historian Lorena Walsh concludes from her research into eighteenth-century Liverpool’s connections with slavery in the Chesapeake (present-day Virginia and Maryland), Blundell was one of seven Liverpool merchants who by the 1720s had successfully established regular trade through investing ‘heavily in West Indian slaving’.

By cross-referencing the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database - available on the Slave Voyages website - with personal and local records, Michelle connects Blundell to ships that cumulatively engaged in fifteen slaving voyages, mainly to Bonny (in present-day Nigeria). These trafficked 4,719 enslaved Africans to the British West Indies - Barbados, Antigua, St Kitts, Nevis and Jamaica. Available statistics reveal that the total death count amongst those forced to board voyages fully or partially funded by Blundell was 801 people. The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database also connects Blundell to a further 27 slave voyages, which transported 6,049 enslaved Africans, of which 1,556 died during the brutal ‘Middle Passage’ – however, it is likely that the majority, if not all, of these voyages were connected to his son, also named Bryan.

Blundell’s four sons and a grandson were involved in numerous other slave voyages until 1780, and further investigation of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database reveals that together the family had a stake in at least 111 voyages, transporting 29,679 enslaved Africans, of whom 5,634 died during the journey. Altogether, the Blundell family donated at least £2,992 to the Blue Coat School, the equivalent today of around £646,000.

Blundell’s journal reveals how his business operated via his most trusted networks of kith and kin, as well as commitment and devotion to his family, whom he supported with substantial finance. He regularly praised ‘God’s assistance’ for the accumulated wealth that enabled this generosity, along with his devotion to the Blue Coat School, to which he gifted £2,000 over the course of his lifetime, ‘a tenth part of which it pleased God to bless [him] with’. His investment in a residential school demonstrates an empathy and compassion towards the town’s poor, orphaned, fatherless and destitute children, however Michelle believes there is an argument that Blundell’s ‘acts of charity and piety were, at least in part, driven by self-interest’: he and his family, as well as other merchant supporters of the school, would personally benefit from the apprenticeship of indentured children. In addition, the strict religious instruction that pupils received helped produce ‘industrious and well-behaved servants, seamen and artisans’. The employment of the children in spinning cotton and picking oakum for a high proportion of the school day also brought considerable income - child labour that was exploited in particular by Jonathan Blundell who employed pupils in his stocking manufactory.

Involvement in the Blue Coat School brought other advantages to Blundell’s political career, conferring status and respectability on him that also helped access Liverpool’s most prestigious social and commercial networks. And, finally, believing in Divine Providence and heavenly rewards for doing God’s work on Earth, Blundell no doubt believed his philanthropic and charitable deeds would secure his comfort in the afterlife.

Michelle concludes that while Bryan Blundell was not ‘incapable of genuine acts of kindness, philanthropy and altruism’, it is likely that ‘a series of multi-layered and interconnected commercial, social, political, cultural and religious factors that shaped him motivated Blundell’s decision to dedicate his wealth, time and legacy to Liverpool’s Blue Coat Charity School.’ Her research makes a valuable contribution to our understanding of this ‘monument to the charity and piety’ of the school’s founders. The building’s story is revealed as a complex and – to contemporary eyes - contradictory and troubling one, in which philanthropy coexists with the barbarity of the slave trade, where generosity and patronage are compromised by self- and familial interest and political expediency.