Back in May, Liverpool-based Ellie Hoskins and Muzychi-based Alevtina Kakhidze came together to create new work in Bluecoat for EuroFestival.

The collaboration was part of Dialogues, a partnership between Bluecoat and Jam Factory Art Center in Lviv.

We caught up with Ellie to find out more about the process and how Alevtina influenced her work.

How did the collaborative process work between you and Alevtina?

I was first introduced to Alevtina’s work by Bluecoat’s curator, Adam. I could see straight away why we’d been matched and loved spending time with her work online and getting an insight into her themes and processes.

Our first proper contact was via Zoom, along with Olena from Jam Factory and Adam. My approach from the very beginning was to kind of take a back seat and let Alevtina and Olena lead with their ideas and ambitions – I wanted Ukraine’s voice to be the loudest, and for my own to respond to that.

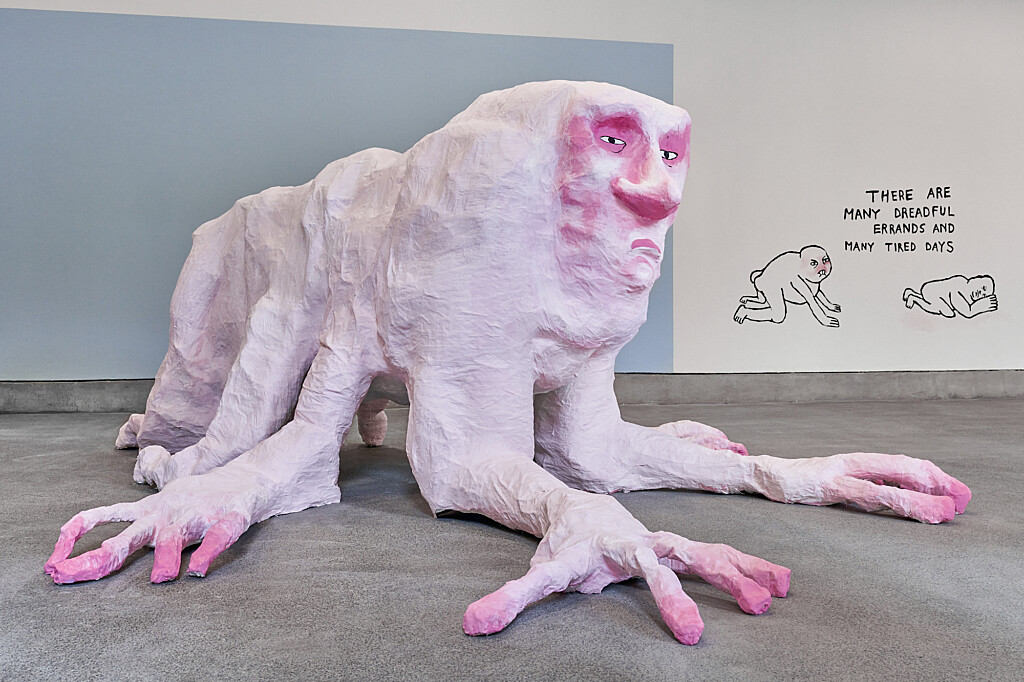

As I listened to Alevtina, one thing that stuck out to me was her mentioning of the tardigrade. She was interested in the microorganism as a symbol of Ukraine’s resilience, and after probing her for a bit more information about what they actually are – and later googling it – I knew this would be an effective unifying anchor in our work. They enter what’s called a ‘tun state’ as a means of coping with hostile environments, and in the tun state they appear to be dead. They can stay like this for up to 30 years. Hearing Alevtina talk about resilience, I was struck by feelings of my own lack of resilience and found myself relating more to the tardigrade in its death-like state.

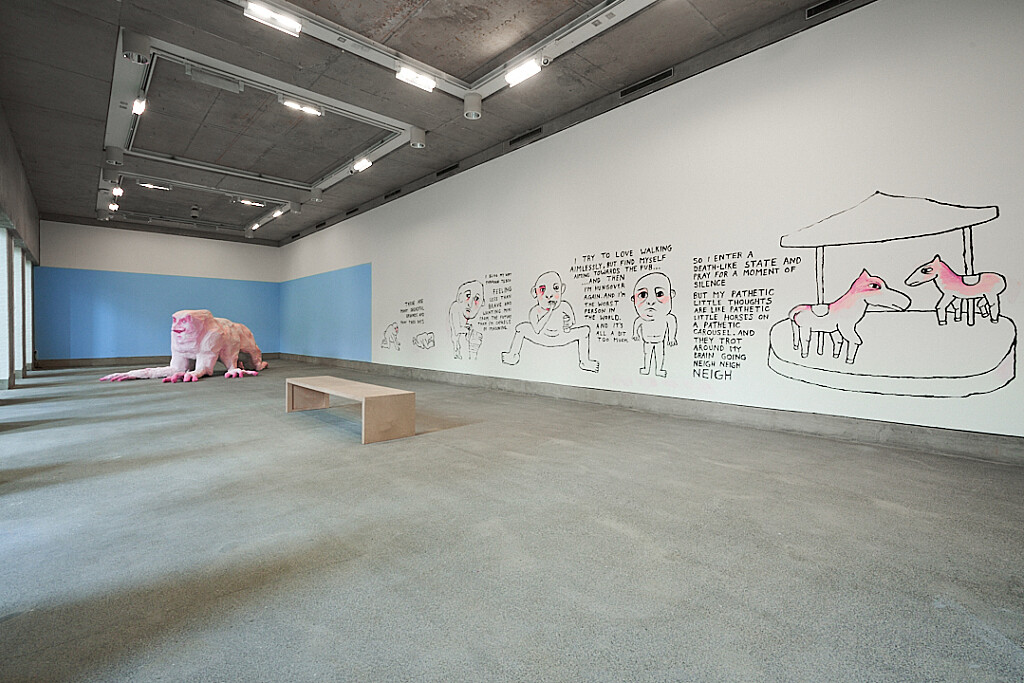

The next time we met was in person in the gallery, with less than two weeks until the show opened and no concrete idea of how our collaboration would end up looking. I started off by making a giant sculpture: my self-portrait as a tardigrade. The rest was left open, and I wanted it to be inspired by the time we spent together in the gallery – the conversations we had, and the wider dialogues they opened.

How did Alevtina influence your work?

As I’ve already mentioned, she introduced me to the tardigrade, which ended up being my starting point. As I was making a huge sculpture of one in the gallery, we had many conversations which ended up inspiring the wall mural I created.

I remember Alevtina showing me a picture she’d taken on her phone of a big mural on Bold Street that said, ‘BE BOLD’. It was interesting because she automatically took that to mean ‘be brave’ whereas I never associated boldness and bravery for some reason. We talked a lot about bravery – about how I couldn’t comprehend the bravery of the people in Ukraine and about how she didn’t necessarily feel brave at all. I understood why she felt like this, and I get that sometimes what looks like bravery is actually just someone dealing with something they have no choice but to deal with, but I couldn’t help but feel like all of the problems and feelings I would usually address in my work sounded absolutely pathetic when compared to the themes of Alevtina’s work.

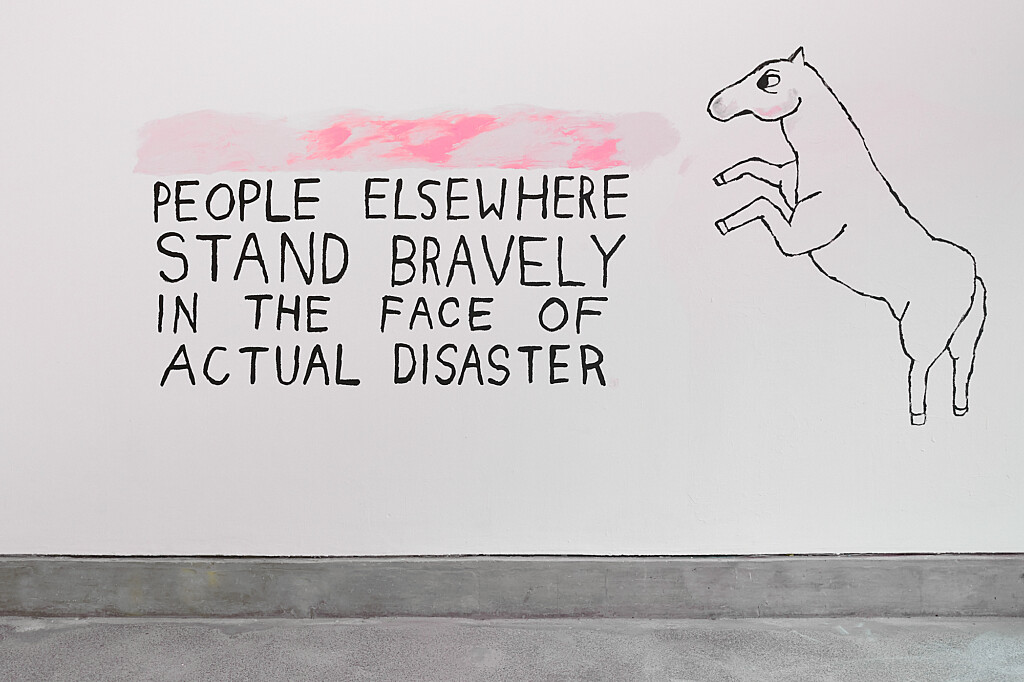

These conversations and thought processes ended up feeding into a drawing and text-based mural that told my truth, whilst also acknowledging the shame that that truth brought me. I referenced dreadful errands, tired days, existential crises taking place in a supermarket, and constant hangovers. The closing statement was: ‘meanwhile, people elsewhere stand bravely in the face of absolute disaster…’ ‘... I sit with the truth and I feel embarrassed’.

What influence do you think your work had on Alevtina?

I don’t think my work had too much of an influence on Alevtina – and this is the way I wanted it to be. We were hosting Eurovision for Ukraine and I wanted her to be able to do whatever she would normally do without having to cater too much to me or my work.

I did offer insight when it came to her Liverpool-centred work though. She would come to me to discuss elements in her audio work to make sure it made sense and she was getting her point across. She also came to me for a second pair of eyes when she was painting her mural. I think all artists doubt themselves whilst working and it’s always so beneficial to have someone else around to tell you that what you’re doing is good and to help you trust yourself.

Have you worked in this way with another artist?

I’ve never worked like this before. I have worked with people whose practices I’ve been really familiar with beforehand, but this was a case of working really intuitively and intensely alongside someone I’d never met. And whilst that could have led to failure, I’m really happy with how the whole thing turned out and proud of how we managed to pull something cohesive together in such a short space of time.

Humour plays a big part in the work you both produce, did you find common ground in this?

It definitely made it easier for us to talk about the work we were creating. We both explored quite heavy and dark themes, and being able to offer each other a relief from this through our dark humour and blunt communication styles made the overall process lighter.

What was the public response to Dialogues like?

I actually work as an invigilator at Bluecoat, and whilst I initially said I didn’t want to work any shifts during Dialogues out of fear that I wouldn’t like what I heard and saw, I ended up changing my mind to go undercover and access the public’s unfiltered responses.

I’m really glad I did because it was all positive and helped me to process what had been quite an intense time. People of all ages and backgrounds seemed to relate to my work, with one woman coming over to me crying because the text element had made her so emotional. I think that was probably a highlight of my artistic career so far – not to sound too sadistic.

And naturally people loved Alevtina’s work. Her direct references to Liverpool were a big hit, with her inclusion of the Lambananas and the liver birds etc providing something for people to instantly recognise and respond to. But more importantly she managed to raise important and political themes about the invasion of Ukraine in a way that felt really accessible. This, paired with my exploration of the shame I felt (and still feel) about how my own ‘problems’ fare in comparison to someone whose country is at war, created a successful overarching narrative across both galleries that people from all walks of life seemed to connect to.

Have you been in contact with Alevtina since the exhibition?

We’re connected online, and I’ve been keeping up with her projects – she seems to be keeping really busy and I’ve loved watching her work develop. I know Jam Factory is open again which is amazing news, and I can’t imagine how good it feels for everyone involved to be able to achieve a slight sense of normalcy amidst everything else that’s going on. I hope to keep in touch and updated in the future.

Will you look to co-create with more artists in the future? What do you think it brings to your work?

I would definitely like to. Having someone to bounce off and to respond to is a good way of limiting my output – I can get overwhelmed by a million little potentials and not do anything as a result, so having a strict deadline and someone else to help guide and limit my output is an effective way of working for me. At the same time I’ve got quite strong visions and a real sense of the kind of work I want to make, so I feel like it needs to be the right collaborator. We need to be able to gel and to be honest with one another if it’s going to work – and luckily Alevtina was a perfect match.

How Tardigrade was introduced in Liverpool through the words of Ukrainian artist Alevtina Kakhidze

"During first online meeting, Ellie became very enthusiastic about this little microorganism — Tardigrade.

She asked a lot of questions and I sent her a bit of information about this organism. It was mainly about: “resiliency of tardigrade is in part due to a unique protein in their bodies called Dsup—short for "damage suppressor"—that protects their DNA from being harmed by things like ionizing radiation, which is present in soil, water, and vegetation”.

I mentioned a Ukrainian scientist, Olena Parenyuk who does research the organism for many years after it was founded inside of the sarcophagus built after the Chernobyl catastrophe to stop radio nuclide pollution. Then Ellie said that she would like to work on this, if I don’t mind that she also will join me with this type of artistic look on resistance, which actually the tardigrade demonstrates in relation to radio nuclides pollution.

When I came to Liverpool we both work to create tardigrades, I was drawing, Ellie was making a sculpture. Then it was more and more talks about also war. Since I came from Kyiv with all my war experience for last 9 years. As far as I understood talking to Adam, talking to Ellie, talking to all people I was in contact with in Bluecoat, everyone was telling to me that they never understood the… how to say… the factor of this war or texture of this war. They saw news. But they just never understood in detail how it’s actually related to people in XXI centuries. If restaurants are open in Kyiv, if I do pay tax, what is with the buses, what is with the schools, art galleries? What does it mean, alerts? How much of time possible to be without electricity, milk, night clubs—they just didn’t know all these practical things.

Coming back to Tardigrade: Ellie made a sculpture of Tardigrade, I did draw it. And when our show was open, the group of kids who were young visitors did draw our tardigrades. In certain moment I understand that community of Liverpool is very open to host any new beings and talented in skills to reproduce them. Tardigrade become a bit alike another being in Liverpool — Lambanana. I mean in speed of reproducing. I hope next time when I come I will meet tardigrades everywhere: on streets, in shops, on t-shirts, as part of common identity of this city."