The Bluecoat was saddened by news of the death of Philip Jeck whose sublime compositions and compelling live performances earned him a reputation as a leading figure on the international experimental music scene for over thirty years.

It was mesmerising to watch Philip, seated behind a pair of vintage turntables and an assortment of minidisc recorders, sampling keyboards and other electronic effects gizmos, coaxing with subtlety and precision exquisite, otherworldly sounds from the worn grooves of vinyl records. Overwhelming, sometimes disturbing and always haunting, these ambient improvisations were unique, a rich layering of sounds that Roger Hill has described as ‘evoking all popular music but none in particular.’ And at the end of his performances, as the crackle of the stylus on the vinyl faded to silence, Philip, after a short pause, would stand and take a modest bow.

Sometimes described as a ‘turntablist’ – and he was certainly a pioneer in the field of sound manipulation using record decks – Philip’s compositions were far away from the floor-filling dance music that was an early influence on him. Visiting New York in the late-1970s, he was fascinated by the mixing of DJs like Larry Levan and Walter Gibbons, and Arthur Russell’s more experimental melding of disco and avant-garde.

It was 1993’s Vinyl Requiem collaboration with Lol Sargent that brought Philip widespread attention, this epic performance involving 180 turntables, nine slide projectors and two 16mm film projectors earning a Time Out Performance Award. Described by The Wire as a ‘glimpse of the future through prisms of past records’, the piece was revisited in Vinyl Requiem Replayed at the Bluecoat 21 years later.

From his adopted home in South Liverpool Philip traveled the world to perform at festivals and gigs, from Melbourne to Milan, Tokyo to Vienna. He collaborated with other musicians including Gavin Bryars, Jaki Liebezeit of influential German band Can, and Jah Wobble (PiL). He recorded 12 solo albums for the Touch label who regarded him as ‘one of the kingpins of our work for 30 years’. In 2009 he won the prestigious Paul Hamlyn Foundation Award for Composers.

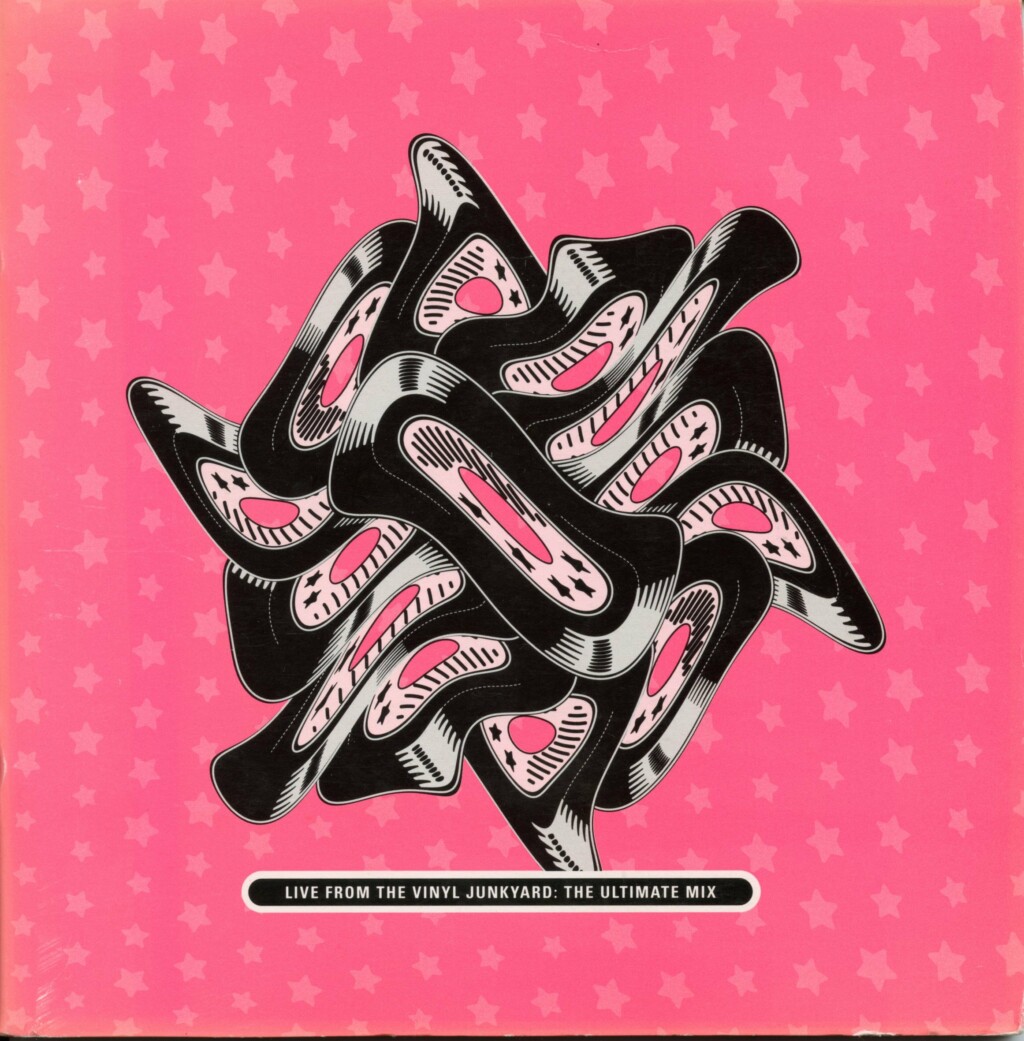

Philip had a long association with the Bluecoat, which deepened once he’d moved to Liverpool. He successfully applied to our 1996 Live From The Vinyl Junkyard commissions, a live art series themed around the supposed death of vinyl records with the emergence of the CD. His proposal, Off the Record, was for a gallery installation comprising 80 second-hand Dansette record-players arranged on a scaffolding structure, each timed to play at intervals, the assorted vinyl sticking on selected grooves. The soundscape built up in this way filled the gallery and was complemented by several live mixes performed by Philip in the space. He later remixed a sound collage that Alan Dunn had created of recordings from the Vinyl Junkyard commissions and a follow up series, Mixing It, released on a vinyl 45 picture disc (‘Take the Mike Away!!’ by The Junkyards) that accompanied the publication Live From The Vinyl Junkyard: The Ultimate Mix.

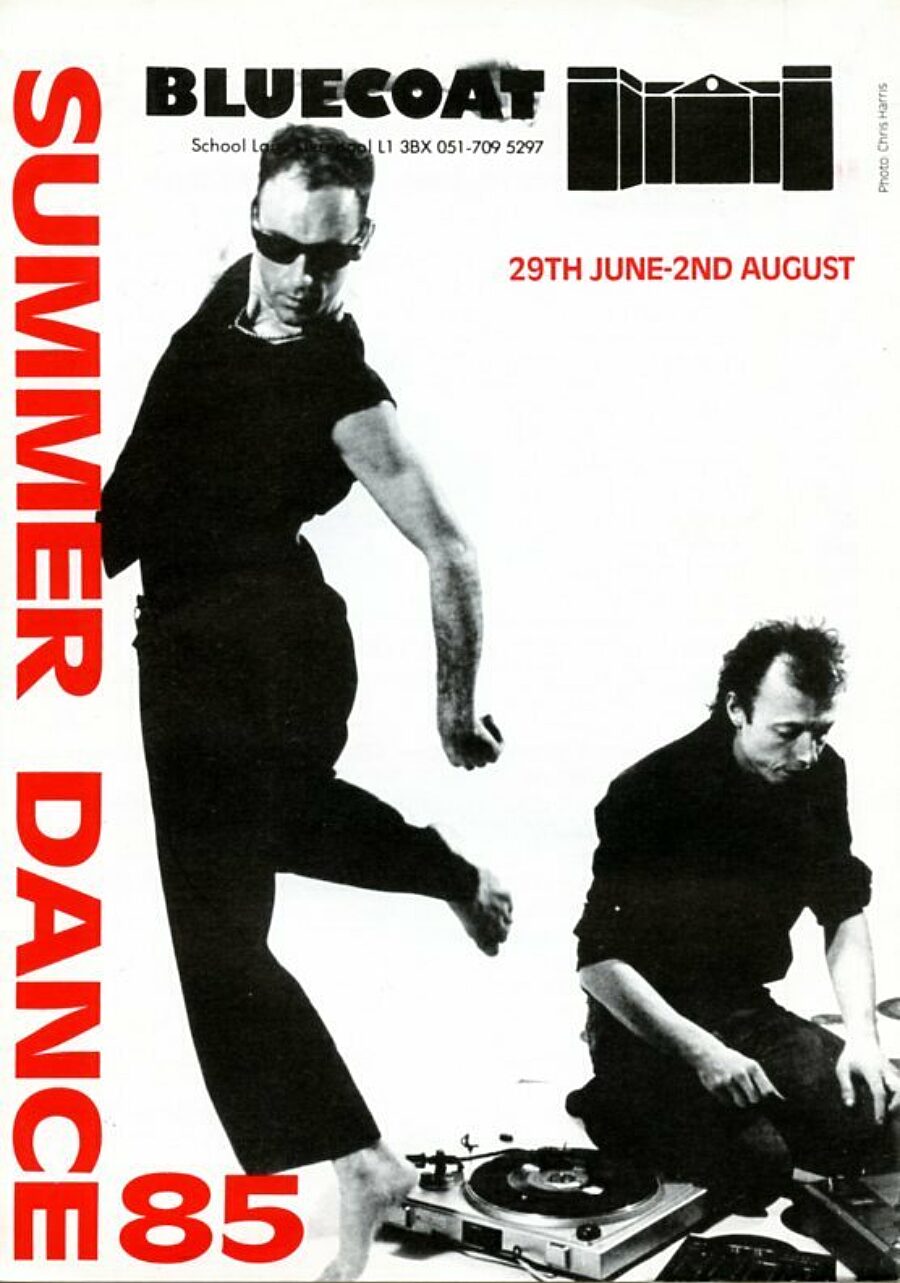

This interface between music and visual art was a prominent strand of the Bluecoat programme, and Philip contributed to it over many years. Originally trained in visual art, his creative practice straddled several worlds, including contemporary dance. In fact, his first Bluecoat performance was in 1985 for Summer Dance ’85, with dancer and choreographer Laurie Booth, which saw Philip ‘lying on the floor with some record-players while Laurie pirouetted around me.’

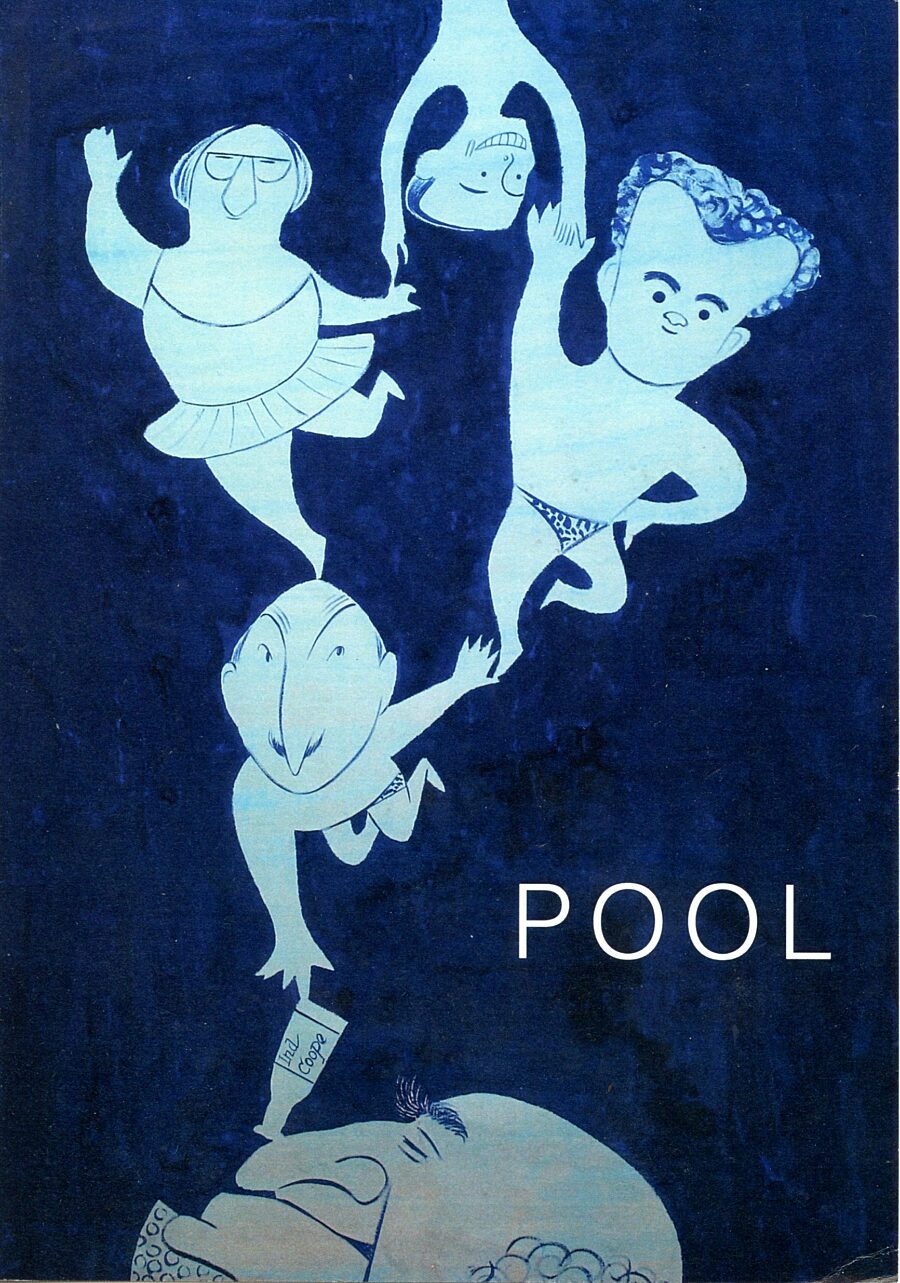

Philip also collaborated with his partner, the dance artist Mary Prestidge, including a wonderfully evocative piece, Maryland, presented in the Bluecoat’s spacious concert hall upstairs (the present bistro), and Pool in 2017, staged for the building’s 300th birthday, in the Sandon Room and its small adjoining outdoor courtyard that had been turned into a swimming pool for the occasion.

Philip was one of eighty or so artists I invited to nominate a hero for a large tableau we created in the gallery in 1997 for It Was Thirty Years Ago Today, an exhibition that reworked the iconic cover of The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper LP. Nestling among a crowd of life-sized cut-out figures including Yoko Ono, Jarvis Cocker, Lee Perry, Frida Kahlo and Minnie the Minx, was an assemblage that Philip had made comprising a record player on a chair and a photo of his favourite singer, Frank Sinatra.

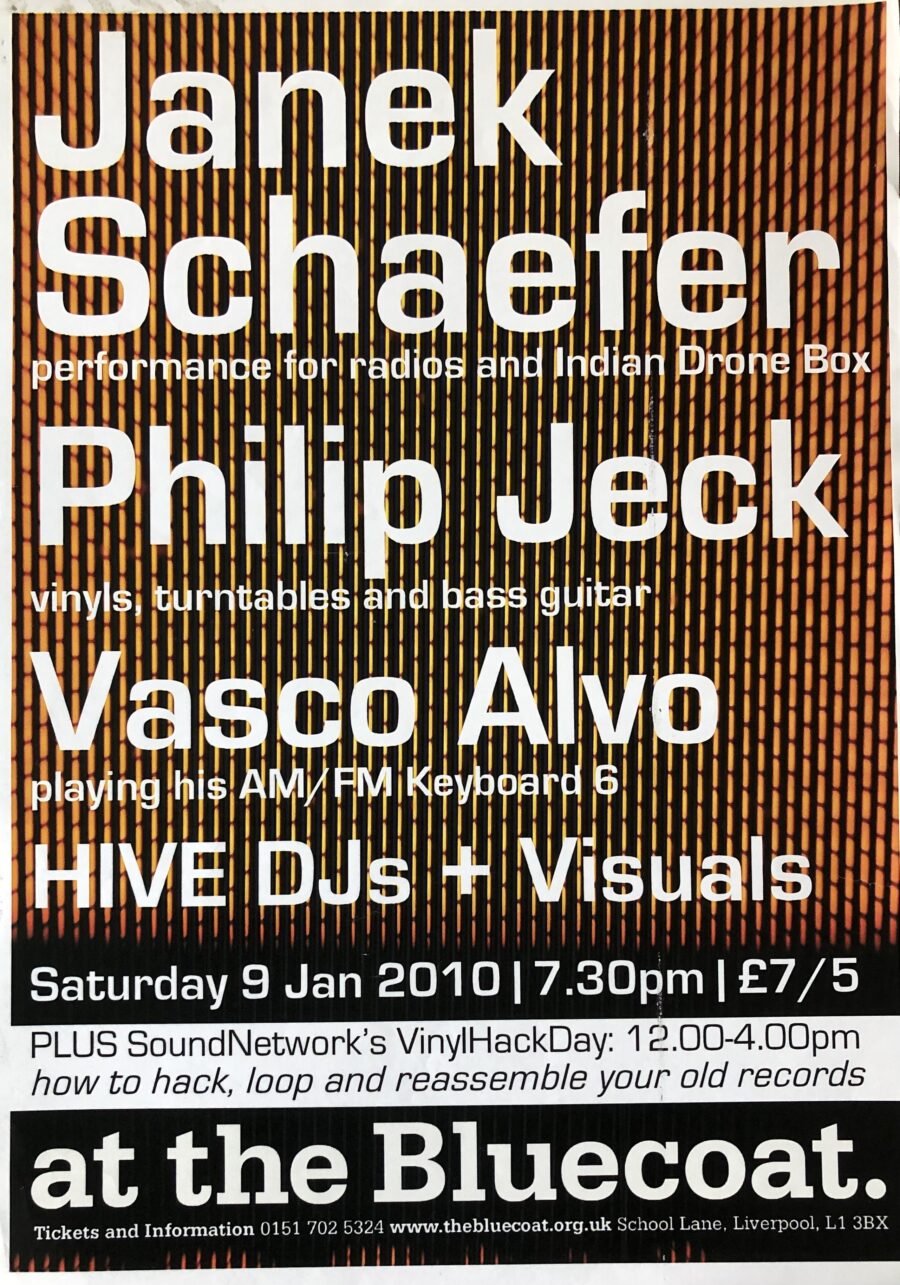

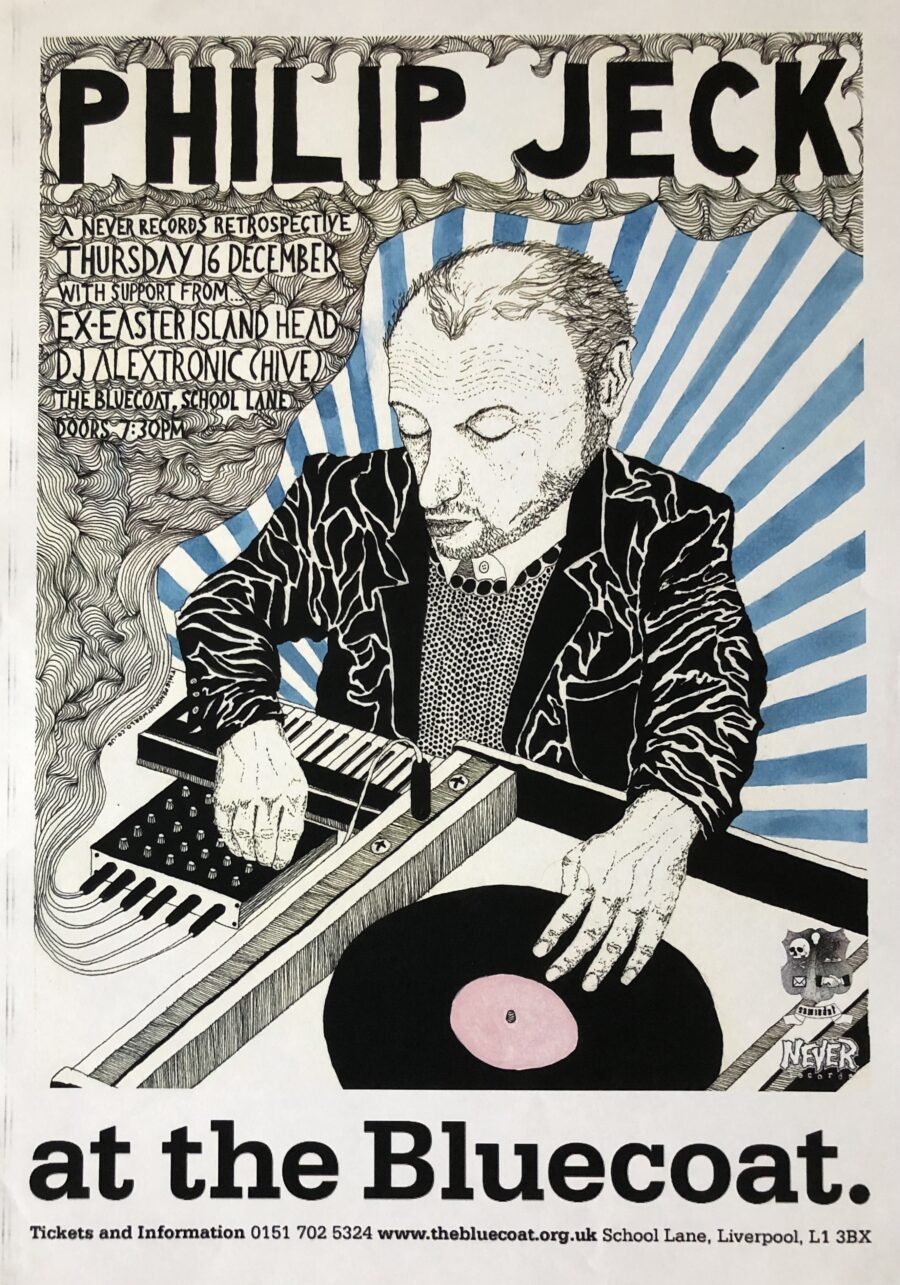

A surprising choice perhaps for such an avowedly experimental artist as Philip, however his musical tastes were extremely catholic, taking in soul, disco, psychedelia, pop, reggae, country and much else. Indeed Sinatra’s subtle intonation and intimacy find echoes in passages of great poignancy that characterised Philip’s performances. Among many presented at the Bluecoat, I witnessed several memorable ones: with Otomo Yoshihide for Frakture’s festival of improvised music (2004), with Janek Schaefer and Vasco Alvo as part of a live programme during Schaefer’s gallery exhibition Sound Art (2010), Rules of the Moon, a multi-media collaboration with poet and musician Rebecca Sharp (2013), and performing as part of a Never Records Retrospective (2010).

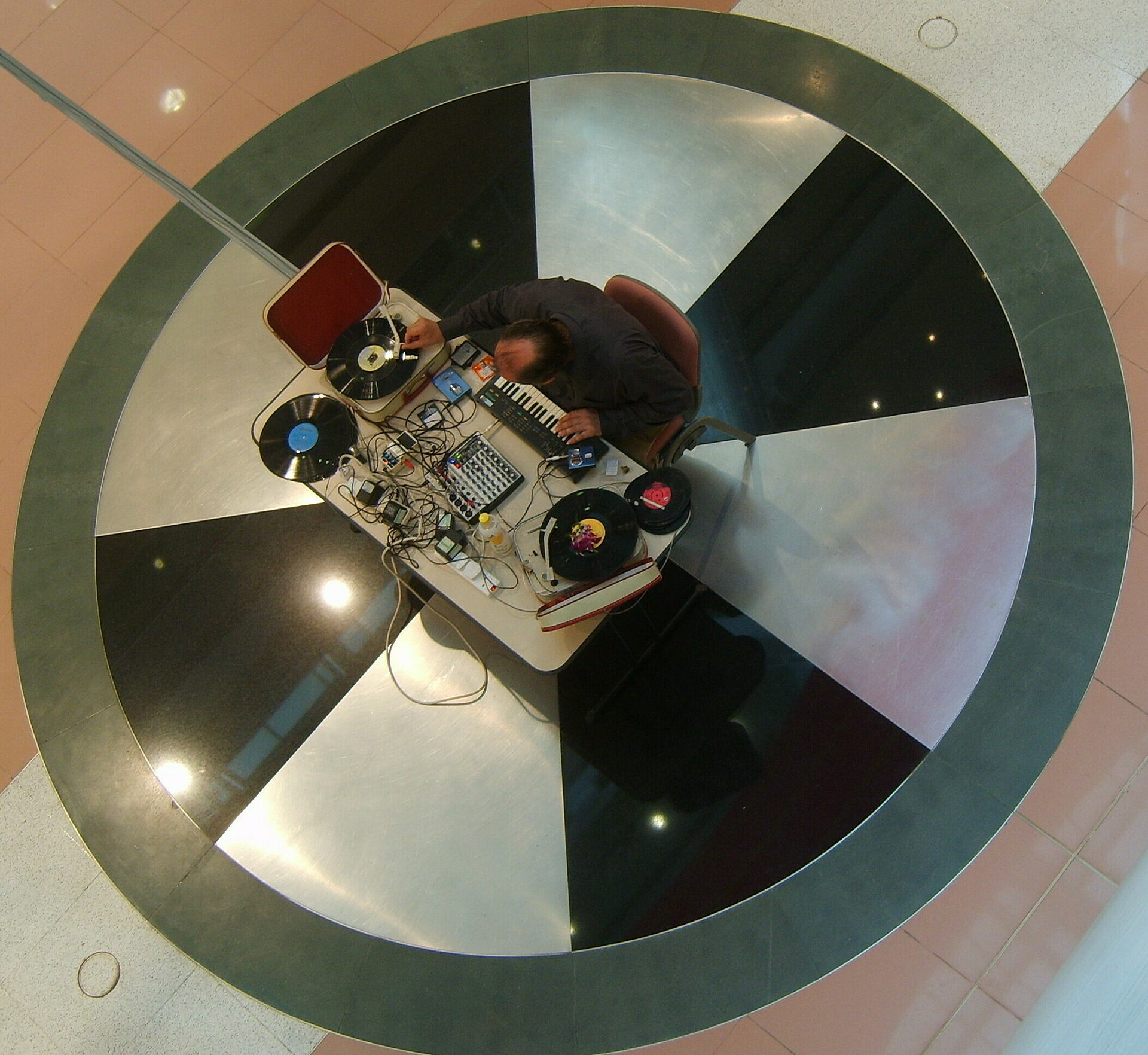

And there was a performance in China in 2006. I’d selected Philip for an exhibition of art from Liverpool called Walk On, part of the 6th Shanghai Biennale in collaboration with Liverpool Biennial. Philip was due to do a live set at the opening but only arrived shortly before the launch, exhausted and jet-lagged, his flight having been delayed and diverted from a European city where he’d been performing (so he was not able to travel with the rest of us from Manchester). The exhibition venue was, bizarrely, a glitzy upmarket shopping mall called Citic Square, completely unsuited for Philip’s sublime soundscapes – acoustically, spatially and in terms of ambience, with shoppers crowding the escalators that linked the several floors of this dazzling cathedral to consumerism.

Understandably, he was reluctant to go on and took some persuading, not least by being informed that the organiser would lose her job if he failed to perform after the speeches. Despite his fatigue, Philip played a blinder, cranking up the volume, spurred on no doubt by an audience intrigued by the odd assortment of seemingly redundant technology, which they captured on their iPhones as they crowded in ever closer to Philip.

In 2016, Roger Hill interviewed Philip for a chapter on music he was writing for our book Bluecoat, Liverpool: The UK’s first arts centre, concluding: ‘He is an eminent instance of a world-respected musical artist who has developed a long and productive relationship with the Bluecoat as his home venue. “It’s a bit like family”, he says. “I don’t think of it as a musical relationship – it is all one.”’ Philip was very much part of our extended family, most recently participating as one of the artists in our ‘Where the Arts Belong’ project, working in a dementia setting. He was a supportive and constructive voice that I personally valued, as the organisation grew and developed its artistic programmes and reconfigured its spaces, four of which he performed in.

Our conversations invariably focussed on our shared obsession with records and pop music trivia, but they would also range far wider into literature, politics and the world of ideas. Alongside his conviviality, and the sublime music he produced, I will remember Philip for his humour. The interdisciplinarity of his art did not extend to stand-up, yet to many of his friends he was the funniest person they knew.

For the Vinyl Junkyard publication, Philip collated snippets from the sleeve notes of LPs into a statement about his work, an extract from which I will end with: ‘…You listen to whatever comes out of now, the past. The sound can drip with well won laurels of acceptance, of transience, of longevity. There is a touch, a method that changes, adapts with the mood of the music, the times. The touch is always personal, passionate: it embraces, repels, passes, returns’.

From all my colleagues at the Bluecoat who knew and loved Philip, we shall miss him dearly, and we send our sincerest condolences to Mary and Louis.